The Astonishing Odour of History

“Every city, let me teach you, has its own smell.” So said E. M. Forster in A Room With A View. As a perfumer I am fascinated by smell—particularly the smells of history.

From that day forth perfume and the scent of the world became my absolute obsession. I acquired all of the rarest and most unusual perfumes and ingredients I could and began to make my own fragrances. I focussed all of my attention on understanding odor: its psychological effect on us and the intensely powerful control it has over our sense of memory.

And that leads us to this list. Herein is a compilation of ten significant places and things and the smells of them. Please be advised, some of the content in this list is disturbing.

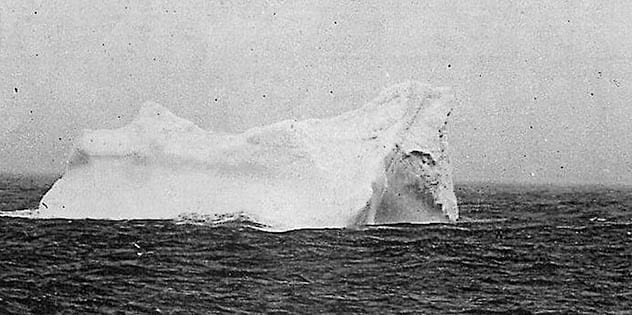

10. The Titanic

In the early hours of the morning of April 15, 1912 the immense body of the Titanic, rent in two, plummeted to its grave on the ocean floor, a mere 5 days after it began its maiden voyage.

The sharp scent of fresh varnish, paint, and newly sawn wood were the initial smells that would have greeted passengers as they boarded the Titanic those five days earlier. At the time, paint was still made with lead and contained high amounts of linseed oil. There would have been the smell of smoke from the coal driven engines and on that fateful night, the wonderful smells of roasting ducks, lamb, and beef, all of which were on the first class menu, would have filled the air.

That same year, the famous French perfume house Guerlain had just released L’Heure Bleue (the bluish hour), which they described thus: “velvety soft and romantic, it is a fragrance of bluish dusk and anticipation of night, before the first stars appear in the sky.”

It was an expensive perfume and in high demand. Its erogenous scent of violets, carnations, and heliotrope would have wafted across the first class deck. And then at 11pm on April 14th, 1912 another smell began to appear: a mineral odor with a metallic edge.

It was the smell of an iceberg. Just as ice in your freezer picks up the various odors of food stored there, icebergs will take on the scent of their surroundings. Interaction from sea dwelling animals contribute to this, as well as the chemical composition of the water from which the iceberg is formed. Recognizing the faintly metallic smell of ice may not have saved the ship, but it might have increased the total number of survivors. In all, 1,300 souls were lost that night.

9. The Holocaust

In 1942 the Jewish Ghettos were disbanded by the Nazi government and mass deportations by train began. There were no stops for toilet breaks, and there were no amenities for those who were ill except for one bucket in the corner of the train car which, needless to say, very quickly was rendered unusable. The entire journey from city to camp was drenched in the stink of vomit, feces, and urine. The foulest aspects of man’s animal side were witnessed, within and without the trains.

For those in the camps that undertook the cremation of bodies, the odor was unlike anything they had smelled before. When meat is cooked for eating, we simply smell the searing of flesh. Not so when a human body is burnt. The sickening stench experienced daily by those in the camps would have been comprised primarily of a beef-like smell from burning flesh, and a pork-like smell from human fat. This would have been accompanied by the noxious odors of sulfur from burning hair and nails, a coppery metal smell from burning blood and iron-rich organs, and spinal fluid which burns with a sickly sweet musky aroma reminiscent of perfume. It is a smell so thick, it can almost be tasted.

And then there was the aftermath. American GIs arriving to liberate the prisoners claimed they could smell the stink long before they saw the camps. “The smell covered the entire countryside . . . for miles around.” One Private said “disease – typhus, dysentery, and tuberculosis – was universal. The crematory had been operating around the clock. . . . [T]he stench of death and of piles of human excrement was overpowering.”

8. Ancient Egyptian Temples

If you have been to a Catholic Church you probably know the scent of frankincense and myrrh for those are the main ingredients in the most commonly used Church incense. The Ancient Egyptians used the same resins in their temples, so it was the penetrating scent of incense that most likely met you upon entering.

Again, like our own Churches, the Egyptians filled theirs with flowers. The most common were lotus blossoms and other marsh plants and reeds. The scent of the lotus is extremely sweet—like fruit. And while that sickly- sweetness would have dominated, the dank marsh plants would have added an underlying scent of dampness and dirt.

Other scented flowers present would have been jasmine with its hypnotic fecal odor of indole, sweet blossoming roses, and the intense scent of fresh mandrake, redolent of dried tobacco.

The next likely odor of the temple would be that of food: offerings to the pantheon of gods. Commonly these were freshly baked bread and roasted meats. At this point you can imagine that the temple would have something of the scent of Christmastime in a modern country village!

At some times of the year, milk, herbs, and vegetables were offered and after a short time these would have lent a faintly sour and strangely appealing rotten scent to the whole. How more perfect a conglomeration of smells could there be? All the odiferous elements of life united in one place.

Combine with that the solemn chanting of ancient priests, the distant sounds of exotic animals kept as pets, and the musical instruments of street beggars and a truly marvelous vision of life in Ancient Egypt emerges.

7. Death

When a person lays dying, one of the most common odors emitted is that of acetone (the very fruity smelling chemical that is used as nail polish remover). In some cases, that is combined with unpleasant odors resulting from the particular illness the person is dying from. Once death has arrived, the body begins to decompose and a number of rather appropriately named chemicals emerge: cadaverine and putrescine are the first and, as their names suggest, they smell of rotting flesh and putrescence!

Why do our bodies release these chemicals? Some believe that it is an evolutionary trait designed to be a warning beacon to others that danger is near. It is believed to spark off the flight or fight mechanism in humans.

Other chemicals are also released: hydrogen sulfide which smells like rotten eggs; skatole smelling like feces; Methanethiol with a smell of rotten cabbage; and dimethyl sulfide with its penetrating odor of garlic, closely related to dimethyl trisulfide which gives the famous corpse flower its putrid stink. Death: a veritable cocktail of vile vapors.

Now how’s this for a disgusting fact: these chemicals are found in many perfumes, and ALL are used as food additives. A little stink . . . can add a lot of beauty.

6. Drugs

Drugs have been used for millennia in their natural form. It was not until the 19th and 20th centuries that we have been convinced to shun them and take medication in a synthesized form by drug companies.

Most of us would probably not recognize the smell of a drug if it hit us in the face (except perhaps marijuana as few people have had a chance to not inhale that at least once).

So what do the most common drugs smell like?

Opium has a sweet slightly burnt marshmallow scent when it is smoked.

Heroin releases a very strong smell of vinegar. The higher the quality the less the odor, but all forms will smell to a certain degree. It smells this way because heroin is produced from opium in a method that requires the use of vinegar. It is that sharp smell that drug dogs are seeking.

Cocaine primarily smells of methyl benzoate, a floral chemical that gives tuberose its rich smell and feijoa fruit its distinctive taste. Drug dogs sniff for this chemical along with vinegar as previously mentioned.

Methamphetatmine (and its unrelated crack) both smell similar to burnt plastic combined with cleaning products like glass cleaner. Frequent use can lead to a person’s skin smelling of ammonia.

5. Outer Space

Space is a vacuum; it shouldn’t have a smell. And yet it does. First off, there is a giant ball of sweet fruity rum smelling gas right in the center of the galaxy (the chemical is called Ethyl Formate).

Why is it there? No one knows. From reports of astronauts we know that other odors of space are also food related with some referring to it as sulfurous and meaty. And another astronaut, Thomas Jones, has reported: “When you repressurize the airlock and get out of your suit, there is a distinct odor of ozone, a faint acrid smell, [ . . . ] also similar to burnt gunpowder or the smell of electrical equipment.”

As for the planets, we can guess roughly their odor due to the chemical composition of their atmospheres. Venus smells of rotten eggs because of the clouds of sulfuric acid, and similarly sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide (the main odor chemical in human gas) is the cause of Mars and, hilariously, Uranus smelling the same.

What about Jupiter? Because each layer of its atmosphere is made up of different chemicals, the scent depends on where you are. In some layers you will smell delightful bitter almonds due to the not-so-delightful hydrogen cyanide, while in other layers (the ones nearer the top) you’ll smell the foul smell of ammonia (cleaning products). That almond-like smell of cyanide actually occurs naturally in flowers like jasmine in the (basically harmless) form of benzyl cyanide.

4. The Animals of Perfumery

From our earliest days, we have combined animal ingredients with flowers and resins to make perfume. Archaeologists have recently been able to smell a perfumed ointment found in Tutankhamen’s tomb and when building the Temple of Minerva in Ancient Rome, the builders mixed saffron and milk into the plaster, which, to this day you can smell when it is damp.

How can we still smell many of these odors? Largely through the use of animal products.

The civet is an odd little mammal often likened to a cat because of its appearance. When terrorized it sprays a foul liquid which is highly prized in perfume making. The smell is reminiscent of vomit and feces but in extreme dilution it becomes floral and is an excellent preservative. It is still used in fragrances today and you have probably worn it at some time. The Civet is also behind the famed luxury coffee Kopi Luwak in which the coffee beans eaten by the animal are extracted from its poop, roasted, and sold to rich wall street bankers.

Another animal product with near mythical status is ambergris. Ambergris is the vomit or feces of the sperm whale (we’re not actually sure which). When fresh it is useless, but when it floats on the ocean for decades basking in the sun, it develops a fine subtle scent of the ocean breeze combined with the wonderful smells of a barnyard. It is unequaled for its fixative properties, particularly these days in which deer musk is no longer permitted. It is worth more than its weight in gold and is only found in the rarest most expensive perfume.

3. The Colosseum

Spectators at the Roman Colosseum enjoyed an enormous number of varied shows: from gladiator fights to exotic animal hunts. And, of course, at a later period, Christians were killed in the Christian persecutions by a variety of methods including being torn apart by wild beasts.

But the Roman people were surprisingly delicate and found the scent of blood unpleasant so the Colosseum had a very clever trick for helping out. Above the heads of the paying guests was an awning (called the velarium), the purpose of which was to protect people from the harsh sun and to keep off the rain should any fall. Additionally, cleverly concealed tubes would continually spray perfumed water over the awning in order to partly minimize the odor of death, but also to moisten the heads of the spectators and keep them cool.

These were supplemented by fountains in the form of statues which also issued forth fragrant water. The primary ingredients in the perfume were earthy saffron, and lemony verbena which, just recently, was outlawed by the European Union for use in any human skin contact products.

2. The Palace of Versailles

First off, the grossly maligned Queen Marie Antoinette of France did not say “let them eat cake” nor any variant thereof. Marie was just a child when the French writer Rousseau attributed it to a queen long dead in a fictional book he wrote.

Queen Marie, and her husband King Louis XVI, lived in Versailles Palace. When thinking of how the French royals lived, we all imagine that life was full of delightful perfumes, pastries, princes, and pompadours but what we don’t imagine are the other two ‘p’s: piss, and poop. Plumbing was rather lacking in the 18th century and Versailles Palace had minimal built in facilities (flush toilets were in the royal apartments only).

As a consequence when nature called, the main option was a little porcelain pot called a bourdaloue. Women had no underwear so they just hitched up their skirts and went for it. But the palace is big and sometimes people would be caught unawares with no bourdaloue in sight. In those cases a quiet corner would suffice. After all, servants would clean up after you later. Combined with the smoke from failing chimneys and a lack of care from overworked servants, the grand Palace of Versailles was a very smelly place to be.

1. The Odor Of Sanctity

Saints have a smell. Well . . . some saints do. The odor of sanctity (Odore di santità as the Italians say) is the opposite of odore di zolfo—the stench of death, sulfur. This odor of holiness comes in a variety of different forms.

For some saints it is a smell that begins to exude from their body after death—often combined with incorruptibility (which is what we call it when their body doesn’t rot). For others it is a sweet fragrance that they unexplainably emit during their lifetime. And for some it is in the form of sweet smelling liquids that leak from the tomb housing the saint’s corporeal remains.

One of the most striking stories of the odor of sanctity is that of 5th century St Simeon Stylites who lived for 37 years on top of a pillar with his skin slowly rotting beneath the objects of mortification he wore. The saint was said to perspire the smell of perfume.

So what does the odor of sanctity smell like? Virtually all cases describe it as sweet, with notes of honey, butter, roses, violets, frankincense, myrrh, pipe tobacco, jasmine, and lilies.

It is also accompanied by a sense that the smell is otherworldly or preternatural. In the 2nd Century, St Polycarp’s body, while burning at the stake, was said to fill the air with the smell of incense, and the incorrupt corpse of St Therese of Lisieux smells of roses, lilies, and violets. The wounds of stigmata are also said to emit a saintly odor.

Source: This article was first published in a modified form on Listverse.com in 2019 by Jamie Frater.